tv Charlie Rose PBS December 27, 2012 12:00pm-1:00pm PST

12:00 pm

intelligent, forward-looking, modern portrait. most people who were working with imagery were trying to breathe new life into 19th century issues. and he came along and said "we're going to make this of an entirely different order." >> with someone of the statue of warhol, there's also a kind of oedipal path where even if you move away from him you will end up meeting him and sort of finding that you do live in his world. >> rose: also this evening, a rebroad cast of our conversation with damian hirst. >> i think without andy warhol i wouldn't have gone so gung-ho. but people say "oh, my god, you've got factory." and you think factories can make dog food, well they can make great cars or something like that. so it's not -- the process is not -- i think it doesn't matter how you get where you're going as long as where you get what

12:01 pm

you want as an artist. >> rose: and you want want what? >> it's different. sometimes i go into my studio and think "look at all this stuff, this guy's insane." one minute i want to spot painting and then the next minute spin painting. it's almost like there's a lot of eyes in here. >> rose: andy warhol, jeff koons chuck close, john currin and damien hirst when we continue.

12:02 pm

12:03 pm

>> rose: andy warhol is considered by many to be the most important artist of the 21st century, though critics and artist debate the meaning of his work, few question his impact on contemporary art. this is the subject of of the metropolitan musician exhibition called "regarding warhol: 60 artists, 50 years." it showcases 45 works by warhol alongside 1200 works by 60 other artists influenced by him. joining me are two curators, mark rosenthal and marla prather. also are three of the artists featured in the show: jeff koons john currin and my good friend chuck close. i'm pleased to have all of them here at this table. let me start with you, mark. somebody once said to me great books begin with a question. do great exhibitions begin with a question? >> well, that's what i hope. the question here is, is andy warhol the most impactful artist? >> rose: impactful rather than

12:04 pm

important? >> i prefer that. i prefer that because i think of his effect being like a meteor hitting the earth and changing climactic conditions, changing river beds, changing ways of working and so influential is to too hard away to put it. if the topography changed in the art world because of andy warhol and you as an artist came along five years later or 15 years later and started working in one of the multitude of ways an artist might work, you may not be thinking well, did this start with say cezanne or pollock or warhol? you're just working amongst the menus of ways that artist work. >> rose: how did you approach this? >> well, i think influences is a good word actually and i think very different than asking the question is he the most important artist of the last 50 years because with influence we were looking at what mark

12:05 pm

suggested. really the influence throughout the culture. the impact of warhol sort of high, low, and everywhere. you know, when i said to a friend, an artist friend, a painter that we were going to do a show about the influence of warhol she said where do you begin? warhol is everywhere. and warhol is everywhere. and there wasn't a moment that the team at the mat sort of came to work in the morning and hadn't had some sort of experience that one warholian. you know, some ad we saw in a magazine, something on a subway, a tattoo of marilyn, a t-shirt. the way that warhol expanded the whole enterprise of art into movies, magazines, television. and so i think the idea of influence is really important when we think about it not just through sculpture and painting but really throughout the culture at large. >> rose: did he influence you,

12:06 pm

chuck? >> well, the first thing i wanted to try and do is move away from him so if that's an influence -- >> rose: it is an influence. >> yi, and he owned famous people so i wasn't going to paint movie stars or anyone like that. >> rose: so you painted your friends who became stars. (laughs) >> yeah, that really screwed up my plan. it was the first -- the first people i painted with were phil glass and richard serra. and the other thing was i -- you know, andy ultimately reduced everything to one squeegee stroke. >> rose: yeah. >> and i like to sit there for four or five months building an image in a very different way. so certainly he kicked open the door along with alex katz and a couple of other people for an

12:07 pm

intelligent, forward-looking modern portrait. most people were working with imagery and trying to breathe new life into 19th century issues. he came along and said we're going to make this of an entirely different order. >> rose: john? >> my influence? >> rose: yes. >> or my perceived influence? i -- i think i was a more reacting against warhol. i must say i never -- i never enjoyed his influence in other artists except for the germans. and i think those artists influenced me much more than warhol directly because i must say that i always found the attributes of warhol kind of unpleasant. like the idea of repetition just -- repetitive and unpleasant and especially the divorcing of the

12:08 pm

direct touch i always found very hard to accept. i understand that it's -- the point of it but i always found it just emotionally hard to accept for my own work. that's why i think i look to the germans more. >> jeff? >> i would think andy's cultural heroes are also part of my cultural heroes. but i think i've always been in awe of his existentialism. of just this -- going from duchamp of indifference to acceptance. where it's so outward and at the same time we're dealing with the self. and the power that, you know, existentialism. >> rose: you decided to do -- 60 artists in 50 years and you decided to draw five categories and see these particular segments of his work and other artists that have flowed into

12:09 pm

that. why that technique? why that sort of architecture? >> well, it's a very large show so you are dealing with 60 artists and 157 works, 51 of which are by warhol. so we did need a way, i think, to sort of control --. >> rose: to give order? >> to give order. and those different thematic approaches were really mark's idea and really, i think, represent five of warhol's main contribution. >> rose: it was a way of organizing one thoughts. >> because you're dealing with so much work. >> rose: but some artists-- like jeff-- are represented in the show more than once. we have four works by jeff koons. we have four works by gerhard richter, several work by pole kas, sometimes a single work like john and chuck, these iconic images. so sometimes artists are represented in different categories so i think there's a kind of fluidity between these

12:10 pm

thematic sections and they're not hard and fast. >> rose: he was a first commercial artist. why did he come to new york and how did he become an artist? >> well, he wanted to be a so-called fine artist. this was the old expression which seems so quaint now. he wanted to be a fine artist but he arrived in new york virtually penniless and found he had a talent for commercial art and he was enormously successful but he dreamed to make in the president realm of jasper johns and robert rauchenberg. >> rose: did he always have commercial success? >> well, he talked about it a lot but i think in the end he's an artist, he had aspirations that artists had. >> rose: you paint because you want people to see your work. >> but he exploded an awful lot of old traditions and ideas. preciousness, all kinds of

12:11 pm

things changed with warhol so that in 1966 he did an exhibition which there were no paintings, this is four years after his first exhibition. he took out an ad in the village voice saying "i'll endorse anything, bring it to me." >> rose: (laughs) >> and he was producing the velvet underground. so he was really changing the conditions of artists' lives, i think. >> rose: you saw him, chuck, right before he died, didn't you? >> yeah. i was going to paint him and he was going to paint me. and he said "i have to go in for this little operation, it's nothing much. as soon as i get out --" but. >> rose: one of those roads not taken. >> yeah. well, i wasn't going to give him one of my pennies for one of his. >> rose: (laughs) >> he didn't know that? >> i said so! i said i'll paint you, but i'm not going to give you one for -- not that wasn't valuable.

12:12 pm

>> no, i know. >> rose: it takes too much trouble for me to make one of these things. but in terms of impactfulness, duchamps had tremendous impact and these people bend the course of our history because they were there. the most important people alter the direction things are going in. and he certainly did. i remember the -- when i was a kid i saw my first pollock and i hated it because it challenged what i thought painting could be. and then i really wanted that rush again. i saw that -- you know, i saw that rush in frank stowe black's paintings and then i saw it when i went in to see andy's show -- >> rose: you're seeing something you have not seen before. >> and often you react against it.

12:13 pm

but when you went into the old stable and it looked like a supermarket storeroom with brilo boxes and everything it -- you know, you say well, what the hell's going on here? because there really hadn't been installation art. >> rose: you're telling a story here beyond just showing the paintings. you interviewed the artists that might have been influenced. why include that? >> i think we thought from the beginning that the show wasn't just about warhol but it was about all of these other artists and to the degree that it was possible we wanted them to endorse the project or at least participate and i tracked down as many artists as i could. i never made it to john currin or obviously some artists who were deceased. there were artists who were deceased but we tried to include statements from artists that i wasn't able to get to. and i think it's really important to show-- and it's

12:14 pm

very clear from just the comments we've heard already-- there are different approaches to warhol and the sense of tension influences a very slippery issue. i think it's a fraught issue with artists. artists don't necessarily want to say "i was influenced by someone" but artists do learn from other artists. so i think the show is incredibly, i hope, nuanced and subtle about the kind of relationships between warhol and the idea that there's a kind of tension and the idea that john sort of approached warhol through german artists that that there are kind of cross currents that influence is -- it can be outright appropriation, it can be parody, it can be theft, it can be all kinds of things. so i really wanted the artist to be on the record in a very honest way about how they felt about this artist. >> and i think with someone the

12:15 pm

stature of warhol there's also an oedipal kind of path where even if you move away from him you will end up meeting him and sort of finding that you do live in his world and you -- and you -- there's no escaping him. >> it is in fact -- >> rose: this is a difficult question to ask but he's not necessarily number one in terms of impact or influence or most important. who else is in the category of those people in the second half of the 20th century? >> it's hard -- (laughter) it's hard. that's why you sort of keep coming back chuck mentions duchamps, obviously, but one of the things that the world was remarkable for was so he came along and did the mona lisa two just the way duchamps had done 50 years before. warhol popularized a lot of things that hadn't been popular,

12:16 pm

like using photography. there had been photography around in painting but very little. >> rose: so what was the reaction at his time when he was doing this, when he first did the campbell soup can and when he first did these things, did the portraiture and did -- >> he became hated immediately and he became unbelievably famous within just a couple of years one of the things that's fascinateing to me is a lot of the people who hated him were not artists and i love to say artists make art history and artists started being touched by warhol no matter what anybody was saying. >> then the curve -- >> larry bell, we have the quote from larry bell, who would expect this in 1963 or '64 saying "warhol's just changed everything." (laughs) rarery bell! >> rose: i forgot he died when he was only 58. >> that's right. far too young. >> rose: let's take a look at some of these.

12:17 pm

the first image is andy warhol self-portrait in 1967. when we see this, what made you include this and how do other people at this table respond to that? >> well, these introduce the show. there's two spectacular paintings from 1967 that were actually commissioned for art expo in montreal, kind of world's fair and they were stacked six high, so four more of them very large in a buckminster fuller geo december i can dome in a theme about a show thematically called "creative america." so they were very brightly colored. had to be seen from a large distance. but i feel that they have such a spectacular impact in terms of introducing the whole idea of the show, of regarding -- he is regarding us. he is the great regarder, if you will. he was the voyeur, they was receiver. and he is looking at us.

12:18 pm

but in this very enigmatic portrait where he's half covered in shadow. his hands in front of his face. so many of his depictions, warhol said "i paint myself to make sure i'm still here." and he's one of his favorite subjects but often his face is obscured. he's wearing sunglasses, he's wearing a wig, he's wearing makeup. so it introduces warhol, i think in the best possible way. >> and you can't go wrong with portraits. (laughter) >> rose: says from the master. let's see the next image. >> well, this is one of the images taken from the newspaper of a nose job, an ad for nose jobs and warhol himself had a nose job and he was obsessed by his own apparent appearance. but this introduced the exhibition having to do with the use of newspaper and, of course, artists made use of newspaper but nobody made use of five-foot

12:19 pm

images taken from the national inkwaier or the "new york daily news," no less. not the "new york times." that isn't where he went. he went to these sources of pop culture again it's a lot like the self-portrait wes just saw where you have two images of the same person and you're forced to start thinking about camouflage which is a very important theme for warhol. >> rose: the next image? >> this is a neo-lithic vase with a coca-cola logo. and one of the interesting things ant war hole's impact is how often artists took warhol's example and turned it into something quite political. really it happened a lot and of course with aweiwei it's as if to suggest that chinese culture has been invaded by the coca-cola logo. so the logo isn't just a matter

12:20 pm

of interest it's an imperialist colonialist image. >> rose: the next image. >> that changed my mind about him. >> rose: it did? how so? >> well, you know, he had a -- i think a way to present the banal and a very different way from andy and they were really difficult. >> i think also you can't see and photograph the terrifying aspect of that piece in particular, how bright it, is first of all, and how -- it's actually physically difficult to look at and it's a vision of perfection that captures the terror and a little bit the almost kind of uns golyness of perfection and. >> rose: you liked it, jeff?

12:21 pm

(laughter) >> having heard all this. >> rose: you sat silently. >> if i think back to andy at the time, i was thinking about andy's -- maybe the g.e. logos, something like that i was playing with hoovers and the idea of a door-to-door salesman with the moovr and there's a death like aspect there, too. >> rose: i read where you talked about going door to door as a child and the experience of it and how you would smell things, see furniture and you'd get a sense of what was going on. >> a sense of acceptance, of the environment and i think of andy's work in that way, of his experience. we're both from pennsylvania so i always -- i feel a sense of that. but, you know, when i think of the work, again, it's a complete kind of externalization and of playing very god like situation.

12:22 pm

playing the creator of -- you can multiply, you can procreate image after image and at the same time you can have aspects of how we interpret images of perfection, defined images into abstraction of life and death. so they're so rich, the whole aspect of what it means to be alive and a sense of our parameters that might take place in drama in this work. >> rose: this is? >> well, this is disaster painting. warhol did a number of these orange disaster and it's an electric chair. in 1963 he was preparing for an exhibition in paris and he said "i'm going to call this show "death in america." but the image of death, the electric chair, is made kind of pretty in these electric chairs but i think there's so much

12:23 pm

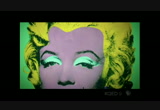

conflict or complexity to the prettiness of warhol's banality. i think banality is really i sort of hinted at. i think there's something dangerous about banalty in a lot of ways. >> rose: the electric chair was designed by spicly. >> rose: that right? art deco furniture? >> unbelievable. >> rose: he was from pennsylvania, too, wasn't he not? >> i think so. >> rose: that's amazing. how did you know that? >> my head is not crowded with a lot of other stuff some of that stuff sticks. >> rose: the next image you'll all recognize, here it is. >> rose: well, mark mentioned "death in america" and warhol said quite clearly that his images of marilyn belonged to the same series and he only undertook the image of marilyn the day she died in 1962. so his images of marilyn-- and

12:24 pm

that was the only image of marilyn that he made something like 200 images of her-- was really very much tied to this sense of morbidity and death that he felt was, as mark said, the ultimate sort of banalty, that death surrounds us. so he took to subject matter like marilyn -- like jackie only after the assassination. liz taylor only after it was reported that she was dying on the set of "cleopatra." and so there is this kind of -- >> rose: that's in between portraits and death? >> it was always concerned about death, his own mortality and, of course, once he got shot. but sidney francis lewis gave their entire collection to the virginia museum and they chartered a 727 and filled it with all the artists so there's roy liechtenstein, jasper johns, everybody was in the plane. every curator, every museum director.

12:25 pm

so andy and phil pearlstein. now, phil pearlstein went to carnegie mellon with andy and when they -- when phillip and dorothy came tneo w york first and andy lived on their floor for a considerable period of time while he's making shoe ads and stuff. so i'm looking at everybody in there and i said "wow, if this plane went down it would pretty much wipe out the art world as we know it." >> rose: and phillip, who was competitive with andy said "yeah and the daily news would say "andy warhol and others." (laughter) but that was how important it was. it would have been andy warhol and others. jasper johns, a lot of people can argue is a more significant artist, but he wouldn't be the top -- >> rose: so this is about fame in america? >> it's about crossing over.

12:26 pm

he had crossover appeal. >> what was the reaction when you pioneered what you were doing in terms of taking photographs and painting for photographs. >> you mentioned photography. it's hard to remember, especially if you're as young as these guys but there was such tremendous animosity towards using the photograph. it was considered cheating i even got spit on by the artists for using a photograph. >> rose: by other artists? >> oh, yeah, figurative artists. so-called eyeball realists. >> a friend of mine was in art school in the early '60s and he said "the photography department was a lonely place. there was one teacher, nobody majoring in it you felt content." >> rose: this was made in about 1969. take a look at this.

12:27 pm

>> well, cindy --. >> rose: what's the direct link between cindy and andy? >> well, there's a lot of sort of pathways as an impact but this is the only one that i believe cindy did that's based directly on a specific person, namely marilyn monroe. but the whole sense of the appropriated image in cindy's work because three quarters of the time you see a image by cindy sherman and you say "i know i've seen this movie, i know where that comes from." maybe you did, maybe you didn't. >> rose: okay, the next one. (laughs) john? >> yeah, well, i could add that these were from pornographic '70s porn from denmark and i think -- speaking of photography one approach -- one approach i had to getting over the guilt about using photography was to

12:28 pm

use -- was to use pornography as a source, as a sort of keep the photograph at a -- something that's essentially photographic and i must say i've always felt -- every artist never gets over the slight guilt of using -- maybe perhaps you have overcome that but the guilt of using a photograph as a -- and i think that's a big part of warhol's effect the way it's screened on in black, that's like the corpse and the color is an attempt to animate it. >> rose: these are the categories "the daily news, from banalty to disaster." the other, celebrity and power. year studies, shifting identities. consuming images and no boundaries, business, collaboration which is the final section. looks at -- another aspect of his life which was partnership

12:29 pm

in terms of other disciplines. >> when everything exploded, in a way, in the '60s, by the time -- he started making films in '63 revolutionary -- >> and he said he wasn't going to make anymore. >> yeah, exactly. >> '66. >> giving up painting. was working with e.a.i.-- experiments in art and technology. he was working with producing the velvet underground, "interview" magazine. he wanted his own television program. he was in advertisements, as mark said. >> rose: he was on "the love boat." (laughter) >> how low can you go? >> that's right. he would sell his soul. so it's this idea of expanding an enterprise into many, many disciplines. >> rose: it was said if you want to look at andy warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me and

12:30 pm

there i am. there is nothing behind it. >> well, there is something about warhol. he was obsessed with fame, he became famous. not just for the work that he made but for the person that he was. he was this strange enigmatic person. there was the look, the social milieu, but he became a kind of cult figure in and of himself. >> rose: but here's what interests me, this is another quote from him. "i still care about people but it would be much easier not to care. it's too hard to care. i don't want to get involved in other people's lives, i don't want to get too close, i don't like to touch things, that's why my work is so distant from myself." >> he didn't like to be touched. >> rose: you never -- i read a sense of -- you were never tempted to try to contact him. >> for some reason-- i guess

12:31 pm

because a lot of other artists did want to interact with andy and we'd go to the factory, i just kind of stayed away. >> rose: why? >> i guess on the exploration of the ideas that i wanted to work with i guess i felt that was better from a distance. but sometimes i'd walk past the factory and look up and maybe i'd see andy at the window and be excited by that. i met him very superficially twice and i enjoyed that a lot. i guess the group that was at the factory at the time-- and maybe it was even the work at the time, charlie" maybe the volkswagen paintings and some of the different image at that moment weren't the images i was interested in. >> rose: what were the ups -- what was the journey of his career after he came to new york in terms of acceptance,

12:32 pm

magnification? >> well, as i say, his first shows were in 1962. one was in los angeles, one was in new york. by 1964 he already showed in paris, he had another show in new york and in the catalog we have a section devoted to how quickly he became famous. and it was astounding speed by today's standards. that even during that time people hated him and so forth. but just to jump far forward, in the '70s there was a lot of questioning even be the people who were interested in warhol had he so sold out? what is left? he did endless commission portraits. there's a funny book on that subject and it sounded like he was like a car dealer hammering his assistants to get commissions! >> rose: to what end? >> well, he loved money. and he did love money and he

12:33 pm

loved hanging out with the kings and the queens and all that sort of thing. >> those commission portraits look better and better. but there's a divide, i think, with having been shot by valerie sew lans any in '68. because there was in this period of hiatus, so there was a kind of apogee in the late '60s and then there was the demise of pop and coincidental with that andy was pronounced dead and really never fully recovered from that and so there was a period. and then this style really changed as he began in the early '70s with commission portraits and particularly with the mao painting. >> rose: jeff, does this resonate with you? pop art is about liking things. >> yes. i think it's about embracing yourself and then going external and, you know, being able to find a sense of confidence in

12:34 pm

the outside world and to share that with people. that they feel more confident about life and so the images are just kind of metaphors for the acceptance of what it means to be human, of other people. it's really not about these objects or these particular images but it's just about that outside world, the acceptance of it. the vastness of it. >> rose: what were his skills? >> that's a good question. i think -- well, he had a fantastic drawing hand. his -- it's a strange painting style. it always struck me that it resembled more scrubbing and cleaning than a kind of lyrical french arabesque. but that itself is incredibly profound in the context of his paintings. i think that -- i would add that i think the influence of his mark has not been so great when

12:35 pm

you see it imitate bid other artists i think it's a downer. so i think he was incredibly good at what he -- i don't think he hid anything. there wasn't a special skill that he didn't show in his work. >> well, unlike de kooning, say, who had a million imitators, straight imitators, there was really no way at that time to appropriate andy. he was the appropriateor. >> rose: (laughs) >> so it would just pass right through him. the original source. and i think that made him more important. that it was not something that was going to be influential in that way. >> rose: mark, thank you for coming. >> thank you. >> rose: that you can very much marla. thank you all. back in a moment. stay with us.

12:36 pm

>> rose: the newspaper "the guardian"'s jonathan jones writes that the whole of recent british art is a footnote to damien hirst's brilliance. he emerged for the first time more than 20 years ago as one of the young british artists. their work came to define the contemporary art scene of the 1990s. since then he has shocked and challenged and thrilled audiences with his work's bold themes and ironic wit. these new exhibitions "complete spot paintings, 1986 to 2012" features more than 300 paintings from his famed spot series. it will take place simultaneously across all of ga gojian galleries in new york, london, paris, london, roam, athens, geneva and hong kong. here's damien hirst speaking about the exhibit as it was being installed earlier this week. >> in any one painting, no two colors are the same. the first painting i did, i did a black spot on it then i never did a black again. i only used colors. and this the gaps between the spots is equal to the spot size

12:37 pm

so that goes throughout. and so i want to create random but random is a very complicated thing. i remember having an argument with a -- an assistant of mine who did six or seven yellows in a row and i went "that's not random." and he said yes, it is. and in the end i sort of avoided that but you would get six or seven yellows in a row. but, you know, i'm sort of -- like i said before i'm a road roe old '50s painter. the idea of -- i love making decisions about color and puting colors next to each other. whenever i look at a painting and put four colors together and choose my favorite four colors and nine colors and you can look at them for ages so i think secretly i like to make those decisions but in the paintings it looks like i'm a scientist and not an artist.

12:38 pm

>> rose: that was done by our producer courtney lits. it opens worldwide on january 12. i'm pleased to have damien hirst back at this table. welcome. you're becoming a regular when you walked in you said that. how are you? >> very good. >> rose: you said as you sat down this is the combination of the huge, mammoth ego. >> exactly. >> rose: you and larry gagosian. >> yes, larry gagosian and mine. >> rose: produce this. >> i think the first time i came on the show larry had two galleries and when i started the spot show there were nine and by the time i did the show there was 11. >> rose: and you had a billion dollars already. >> (laughs) >> rose: let's talk about these. it obviously began with one painting. what was it? you love color. but what got you to do a spot and you instantly make it -- >> i always like to throw paint around and mess -- i was into

12:39 pm

kind of -- i was taught by '50s painters not in england but, you know, kind of gestural painters who were that you paint how you feel and if you're happy you do orange and if you're sad you do purple and i kind of believed in that and believed it was the truth but then i got into conceptual art when i went to school in england and i realized it wasn't the truth. but i loved color so i just created a kind of grid where i can make those decisions but the end result was never -- they're not -- you're not going to get -- it's denied, anyway. >> rose: how many of there are these? >> we worked it out. in total about 24 years i think it's 1,500 approximately paintings. about 60 a year i've been doing for 24 years. >> rose: you did the first five yourself? >> looking in the gallery i think i might have done the first 25. i said five but i've noticed a few others. (laughs) where the spots are more like squares. >> rose: can you tell? >> yeah. through the years, when i first

12:40 pm

made them i thought i'm going to do these paintings and i want to look at them through a distance like a crazy machine. no eyes. but close up i thought i wanted have eyes, and holes where i used the compass to draw the circles but over the years it got more and more perfect so now you can't tell they're man made. it's important that man made -- i don't want them to look machine made. >> rose: you've always said that. the idea that everything's not done by you is something that you have been totally transparent about because you believe what? >> the best way to look at it is the architects don't build their own houses, do they? in my mind when i did the first spot i said i wanted this to be an endless series. when i do a show a do about -- i like to see 30 works or something like that. so show after show you want to do these paintings and if you do them yourself there's not enough hours in the day. >> rose: the fact that this is a global exhibition, are you going to go from town to town to town?

12:41 pm

>> yeah, i'm going to l.a. after this for the opening. but we've had them open simultaneously so i can't be in all the same places at the same time but we'll have a closing in london. i'll make sure i go to the shows and do a dinner, small dinner. start off with small dinners but then i find out there's going to be a d.j. >> rose: i know, i know. (laughs) what does it mean to you? >> i don't know. i mean, you try and do many, many, many things when you're making a painting. i always think paintings are crazy sort of meaningful things. we've come a long way since we were living in caves. even when we were in caves you want something on the walls but for me spot paintings, they never get boring. i've been doing it for 24 years. i always used to think well if i put this outside a bar when it was closing would it still be there in the morning? if it is it's not a good painting. >> rose: do you characterize them as deceptively simple? >> i don't think they are simple. it's a simple structure, a grid, but once you put the colors in there it never keeps still.

12:42 pm

all the grays, the ideas are simple, aren't they? >> rose: sure, yeah. simple and if you can make them simpler the better they are. >> yeah, it's like one plus one equals three. you try to make something that amounts to more than its ingredients. >> my friend robert hughes -- >> yeah, my friend, too. maybe not my friend. (laughs) >> rose: well, you'd like him. he said these were silly abstractions. >> yeah, it's funny because when i was a kid i remember growing up on the shock of the new you know? and thinking wow. so to come full circle and go through all that and ghetto the point where robert hughes doesn't like the paintings you think that's just nuts. >> rose: (laughs) >> maybe they're too shocking and new. >> rose: does it bother you at all? a little bit? maybe? >> it's like success. you have to go, well, how do you measure success and you can't measure whator people say, you have to measure in the your own. >> rose: how do you measure it? >> like i said, the idea about

12:43 pm

the pub. you put it on the floor outside the pub and if it's gone you know you'll be successful. but i red a goya book when i was on holiday and i thought all right, i'm not working, i read a painting on goya by robert hughes and i got five pages in and he said "goya wasn't like damien hirst." i couldn't read the book. i don't like him for that. (laughs) spoiled my reading. that's the only bad thing. >> rose: do you read a lot about other artists? >> when i start it's -- i remember when i was young i went into the leads art gallery and looked into the books. i'm going to read this before i can start but you can only read so much can't you? >> rose: that's true. >> i never dream there'd be a book with my flame on there. >> rose: how many books of your name are in the leads library? >> i don't know, maybe more than one. >> rose: so tell me where you are for the evolution of a life in art. leeds.

12:44 pm

>> i don't know. i feel very lucky. i've got a lot of freedom i've made a lot of work. >> rose: made a lot of money. >> made a lot of money. >> rose: interestingly, you and andy warhol have made that sort of acceptable. >> yeah, i think without andy warhol i wouldn't have gone so gung-ho. a lot of people say "oh, my god, you've got factory." and you think, well, factories can make dog food or they can make porsches or great cars or something like that, you know? so the process is not -- i think it doesn't matter how you get where you're going as long as where you get what you want as an artist. >> rose: and you want what? >> it's different. sometimes i go in the studio and i think look at all this stuff, this guy's insane. one minute i want to spot paint and the other minute i want a spin painting and i kind of imagine it's almost like there's a lot of crys in here. >> rose: what do you think people don't get about the spot painting? >> probably the simplicity. i think -- it's funny -- there's

12:45 pm

a big difference between art and craft as well. i get asked a lot where people go "you don't paint your own paintings." but that's never been a problem to me. in the same way i said architects not building their own houses. but the ones i did paint myself sell for more money. so i it's a strange quirk of the market tooo me. i always go for perfection. the ones that i paint look kind of awkward. >> rose: what about posters? >> what about posters? (laughs) >> rose: what do you think of posters? >> i love them. i had this thing where somebody would -- i'm sort of torn when they go which do you prefer, the mona lisa painting? would you like to be the guy who made the mona lisa or do you like the postcards and t-shirts and earrings. >> rose: you said postcards. >> i like them both. >> rose: do you say postcards when it's posed that way or not? >> i suppose. you know the postcard has the biggest impact. there's something amazing about the unique wonderful painting even though you can't see it because it's behind bulletproof

12:46 pm

glass. >> tell me about this jacket you have on >> i don't know. it's -- it's japanese design. it's called "mastermind." i've found it after i did the diamond skull. that's me! >> rose: is that your biggest creation, the diamond skull? >> i said recently in an interview probably i could pick my top four, what to take from a burning building or whatever you say. >> rose: what would they be? >> "shock." >> rose: shark? you couldn't take that. >> well, it depends where the fire started. the shark, the diamond skull, a thousand years and a spot painting. >> rose: those would be the five you'd rush to? >> the four, yeah. >> rose: so what might you be doing ten years from now? >> god i have no idea. i have loads of crazy ideas working at the studio. >> rose: you constantly experiment? >> lots of things don't make it into the galleries. as an artist you make things in

12:47 pm

the studio that are nuts. i'm playing with the idea of primate paintings where i get monkeys in the studio. >> rose: these are live monkeys? >> i'm thinking about it. but i think i might make the paintings and work with the monkeys. it's not going to be just straightforward. i want to make the paintings that look like a little bit better than monkey paintings so you go are they by monkeys or not by monkeys? the whole idea i'm thinking is this nuts or is this a good idea? >> rose: finish this sentence for me. "would charles saatchi damien hirst would be --" >> charlie rose. (laughter) i don't know. without charles saatchi -- >> rose: does that mean charlie rose with charles saatchi would have been damien hirst? >> i would have been making work that was smaller. you know, cork street in london, there were painters like peter blake and richard who were making small paintings and saatchi, i went in there and i was blown away by the scale. >> rose: this was the 1990s probably? >> i think for me and my generation of art that's what

12:48 pm

made it work globally. >> rose: i'm trying to get him on the show. would you weigh in for me? >> yeah, he doesn't like t.v. though, does he? last time i saw him -- >> rose: he likes me but doesn't like t.v. >> i don't know what you can do. i'll dress up at him. >> rose: come in and be charles sach chri. do off the charles saatchi impression? >> i don't know. last time i saw him he was so disappointed that i stopped smoking. >> rose: you've got more willpower. >> well, it's brand loyalty. >> rose: 1991. so -- >> yes, when i first started them they began with a, the first year this from late 1991. >> rose: this is controlled substance key painting. >> yeah, well i -- so i did a series for controlled substances because all the paintings were

12:49 pm

named after drugs and these were the controlled substances. >> these were the drugs i need for my cold. >> you're not doing good. >> rose: the next number three is -- take number three. what's that? >> very few squares. so that's an odd one. >> rose: why do you do very few squares? >> i don't know, it would be awkward. a square seems perfect. the first ones i was doing like 9 x 10 spots, 10 x 11. >> rose: and the next one is 1995, right? >> yeah, that's a controlled substance painting and that's the key painting that goes with it. >> rose: okay. this is five. let's see it. you like that? >> i like them all. because what i found is when i look at any painting, if i have it on the wall in my house i'm always picking out four spots, nine spots. nine together just works really well. >> rose: what's on your wall at your house? >> i did have a spot painting.

12:50 pm

i have the tendency to self-determine so i get bored with them. >> rose: didn't you sell one at one time for, like, 300 pounds then have to buy it back and pay twice as much. >> yeah, i did with with saatchi i bought a lot of work back. >> rose: you once had an exhibit in which you sold everything at auction do you remember that? >> oh, yeah, 2008, yeah. charles shook my hand and he said "i love that." >> rose: you didn't put in the a gal voy they could see it. >>. you just sold it. >> just so many people through my career said "you cannot sell, you can't go to the auction houses, you can't go to auction." a lot of things i've done have always been about -- i've just said why? why can't you do that? they said you can't be an artist under a curator and watch it do this. i guess it's childish, really. new hampshire is how much did you make out of that? >> like $200 million or something. it was the day that lehman brothers collapsed. that morning, though, i woke up and got the newspaper and it

12:51 pm

said "black monday." and i just went, oh, well, we're done. and people say to me "you're so smart." i said it's not smart. i was like whoo. so close. it could have been so wrong. >> rose: so what do you do with all the money?. >> i've bought a lot of art. >> rose: have you really. >> i've got -- >> rose: what do you collect? >> i bought bacon who's a great friend of mine, francis bacon. >> rose: you knew him well. >> i was around him but i never really spoke to him. >> rose: lucian freud, did you know him well? >> i got to know him more. >> rose: i once had lunch with lucian and talked about bacon. it was the most amazing conversation i ever had with an artist. >> rose: >> he's such a great guy, lucian. when i first met him i did the fly piece and he said to me "damien, i think you may have started with the final act." >> rose: (laughs) >> you're never going to make a good piece after. that. >> rose: speaking of final act, there's something about you that -- you honor death. >> i've got a house in mexico.

12:52 pm

i don't know if honor is -- >> rose: well, help me out. >> i think in life -- i mean, i was taught by my parents to confront things you can't avoid and death is one of those things and i think, you know, it can't be something -- >> rose: can you paint death? >> i think painting is all about life, really. death's -- >> rose: celebration. >> a black painting, you know? i think death is not painting. >> rose: yeah. so life is painting and death is not painting. >> there's a great quote by beckett where he says "death doesn't require us to make a day free." i love that. >> rose: (laughs) you like beckett, too? >> yeah, of course. >> rose: all right, let's look at eight. >> another controlled substance painting. in the beginning i always made the grid the same. >> rose: 2005. >> yes, in the beginning i started with -- i made all the decisions of -- big decisions about what the whole thing was

12:53 pm

going to be so the spots are equal to the gap between the spots, no two colors are the same and i think this is the first one where i just turn the grid 90 degrees and you get like the grid's off center. >> rose: speak to this idea that an artist needs to get the public's attention. >> i always think that you have to get people listening to you before you can change their minds. i suppose when i came into -- my idea originally was, you know, i'm just going to paint and i'm going to put the paintings in the corner of the studio and if i get discovered great and if i don't maybe i'll be lucky and they'll discover it after i'm dead. >> rose: a kind of van gogh thing. >> i suppose. then you look at the world and you think that's not what the world's about. at my art school in london they just said "you need an audience." we worked it out. all you have to do is get a white building -- a building, paint it white, buy wine and invite people and your work starts to live. anyone can get an audience. once you do you say "what am i

12:54 pm

12:59 pm

[ chimes rattling ] >> ross: if you need me, call me. >> [ cheering and applause ] >> no matter where you are, no matter how far, just call my name. i'll be there in a hurry. on that, you can depend and neve >> man: right now, though, a cloud, a literal one, is hanging over the packed crowd as a severe thunderstorm watch -- >> woman: this'll be an event, the kind of thing you tell your grandchildren about. >> man: this is a landscape of humanity -- not thousands, hundreds of thousands --

251 Views

IN COLLECTIONS

KQED (PBS) Television Archive

Television Archive  Television Archive News Search Service

Television Archive News Search Service  The Chin Grimes TV News Archive

The Chin Grimes TV News Archive

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Open Library

Open Library American Libraries

American Libraries TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11